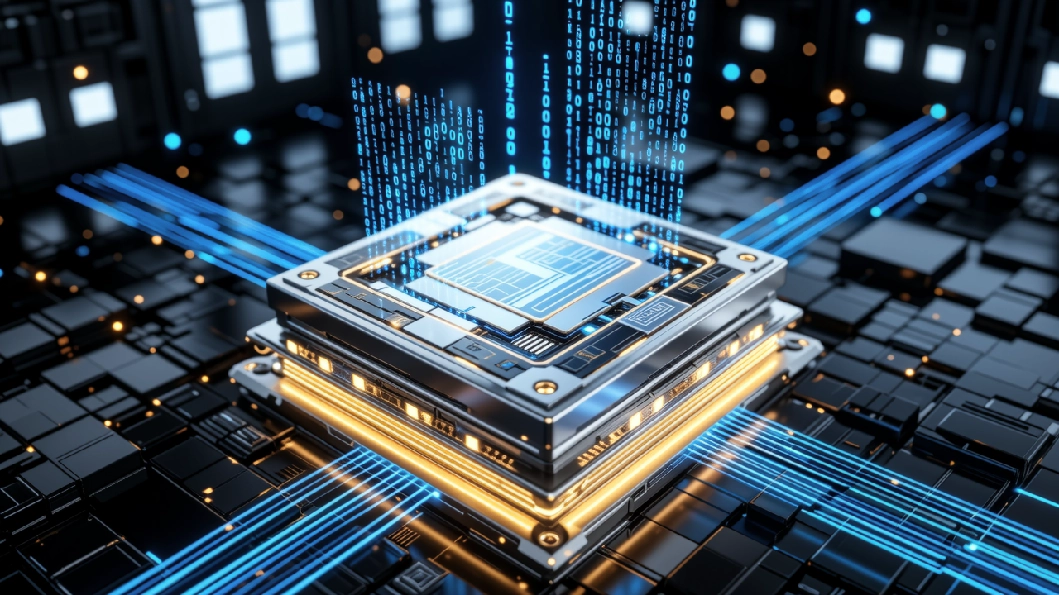

The U.S.-China chip war extends far beyond trade friction, representing a comprehensive strategic competition concerning national security, technological hegemony, and future economic development dominance. Its essence is a contest for core technological supremacy between an established power (the U.S.) and a rising power (China).

I. Background and Root Causes

-

Technological Dependence and Security Anxiety:

-

As the world’s largest chip market, China has long relied on imports, especially for high-end chips. This dependency is seen as an “Achilles’ heel” for its national security and key industrial development.

-

The U.S. views China’s rise in the semiconductor sector, particularly through industrial policies like “Made in China 2025,” as a long-term threat to its technological leadership and national security.

-

-

Military and Technological Competition:

-

Modern military equipment (e.g., F-35 fighter jets, drones, hypersonic weapons) and cutting-edge technologies (e.g., AI, Quantum Computing) heavily rely on advanced semiconductors. The U.S. aims to curb China’s ability to enhance its military capabilities through these technologies.

-

-

Ideology and Model Competition:

-

The U.S. criticizes China’s state-led industrial policies and alleged intellectual property violations, arguing they distort the global market. This competition also reflects a clash between different models of economic development.

-

II. Timeline and Key Events

| Time | Key Event | Impact and Significance |

|---|---|---|

| 2018-2019 | The U.S. places Huawei and other Chinese tech firms on the “Entity List” on national security grounds, restricting their access to U.S. Technology. | Marked the opening salvo of the chip war, targeting specific companies with precision strikes. |

| 2020 | The U.S. escalates sanctions against Huawei, cutting off its chip supply and requiring global chipmakers using U.S. technology to obtain a license to manufacture for Huawei. | Escalation of the conflict, aiming to completely sever Huawei’s access to advanced chips. |

| Aug 2022 | The U.S. passes the CHIPS and Science Act, providing $52.7 billion in subsidies to attract semiconductor manufacturing back to the U.S., but recipients cannot significantly expand advanced chip production in China. | Building a “U.S. Camp”, using subsidies and “guardrail clauses” to push global chip supply chains to “decouple” from China. |

| Oct 2022 | The U.S. Commerce Department issues sweeping new export controls, restricting exports of advanced computing chips, manufacturing equipment, and related talent services to China. | Full-scale escalation of the war, shifting from “strangling supply” (chips) to “uprooting capability” (manufacturing), attempting to lock China into older generations of semiconductor technology. |

| 2023 | Japan and the Netherlands join the U.S. sanctions regime, restricting exports of high-end lithography machines and other key semiconductor equipment to China. | Forming a “Containment Alliance”, as the U.S. rallies key equipment-producing countries to form a blockade. |

| 2023-Present | China accelerates its self-sufficiency drive. Huawei releases the Mate 60 Pro with a self-developed 7nm chip, and SMIC works to increase advanced process capacity. China also initiates export controls on critical raw materials like gallium and germanium. | China’s Counterattack and Breakthrough, demonstrating progress in autonomy and leveraging its dominance in key raw materials for countermeasures. |

III. Core Dimensions of Competition

-

Manufacturing Equipment:

-

Core Pain Point: ASML’s EUV lithography machines are essential for producing 7nm and more advanced chips, which China cannot obtain.

-

U.S. Strategy: Ally with the Netherlands and Japan to completely block China’s access to advanced manufacturing equipment.

-

-

Chip Design Software & Architecture:

-

Core Tools: U.S. companies dominate EDA software and ARM/X86 architectures.

-

U.S. Strategy: Cut off access to the latest EDA tools, restricting China’s ability to design advanced chips.

-

-

Manufacturing Capability:

-

Core Gap: China’s most advanced foundry, SMIC, still lags behind TSMC and Samsung in mass production technology and yield for leading-edge nodes.

-

China’s Strategy: Mobilize national resources to support SMIC and others, accumulating capital and technology in the “mature process” market while gradually advancing towards more advanced nodes.

-

-

Talent & Ecosystem:

-

The U.S. restricts talent exchange in semiconductors and seeks to exclude China from global technical standards and supply chain alliances.

-

IV. Current Situation and Impact

-

Fractured Global Supply Chains:

-

The world is moving towards a “one market, two systems” structure – a “China supply chain” and a “non-China supply chain.” Global firms face pressure to choose sides, leading to higher costs and reduced efficiency.

-

-

China’s Dilemmas and Breakthroughs:

-

Dilemmas: Face significant obstacles in R&D and production of advanced processes (7nm and below), making it difficult to catch up in the short term.

-

Breakthroughs: Accelerate import substitution in mature processes (28nm and above), and make progress in chip design, some equipment, and materials. Leverage its vast domestic market to drive innovation.

-

-

Challenges for the U.S.:

-

Massive subsidies cannot quickly rebuild a complete semiconductor manufacturing ecosystem, facing challenges like high costs and talent shortages.

-

Overly broad sanctions may hurt the revenue and R&D investment of U.S. chip companies, creating a scenario where the U.S. also suffers significant losses.

-

V. Future Outlook

-

Prolonged and Normalized Conflict: The chip war will be a “technology marathon” lasting for decades, unlikely to end easily due to changes in government.

-

Diversification of Focal Points: Competition will expand from logic chips to memory chips, third-generation semiconductors, chip architectures (e.g., RISC-V), and other new areas.

-

China Accelerates Self-Sufficiency: Regardless of the external environment, China will steadfastly advance self-reliance across the entire industrial chain as a matter of national strategy.

-

Dynamic Game of “Containment” vs. “Counter-Containment”: China will seek loopholes in the U.S. blockade (e.g., through third countries), while the U.S. will continuously patch its rules, leading to ongoing escalation.

Conclusion

The U.S.-China chip war is the central battlefield of 21st-century geotechnological competition. It has transcended commerce to become a microcosm of the comprehensive national power contest between the two nations. This war will not only reshape the global technological and economic landscape but also profoundly influence the direction of the world order for decades to come. For China, it is a forced “breakout battle”; for the U.S., it is a “blockade operation” aimed at maintaining hegemony. The outcome will depend on both sides’ endurance, wisdom, and pace of technological innovation.